These slides are from a talk I gave earlier this week to my lab, describing two papers we published recently:

(slides are published on Nature Precedings: you can vote it here)

Bioinformaticians frequently use data and annotations from scientific databases, like KEGG or Uniprot. However, it is difficult to know how much accurate this data is, and to which extent it can be used for a large scale analysis.

So, the talk is about this. Let’s say you dedicate 6 months of my PhD thesis to accurately study and annotate a set of genes, like I did for the N-Glycosylation pathway: How many errors or unclear annotations do you expect to find in scientific databases?

Another topic discussed in the talk is the issue of how to report an error to a database. Many databases do not have a transparent system to report errors, so any incongruence is correct behind the scene, generating some issues to reproducibility. Moreover, the process of reporting errors to a database is basically not acknowledged by the scientific community, and this is unfortunate because if it were more recognized we could have better annotations in the databases and a more active scientific community.

References:

-

Dall’Olio GM, Bertranpetit J, & Laayouni H (2010). The annotation and the usage of scientific databases could be improved with public issue tracker software. Database : the journal of biological databases and curation, 2010 PMID: 21186182

-

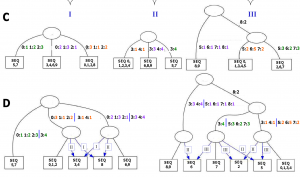

Dall’olio GM, Jassal B, Montanucci L, Gagneux P, Bertranpetit J, & Laayouni H (2011). The annotation of the Asparagine N-linked Glycosylation pathway in the Reactome Database. Glycobiology PMID: 21199820